Throughout human history, age patterns have followed a predicable trend: Parents would give birth to large numbers of children, not all of whom would reach adulthood; and as a generation moved from childhood to adolescence and through adulthood, more and more would succumb to death from illness, accidents, or conflict. The result was a pyramid-shaped age distribution, with large numbers of young people and fewer and fewer people attaining the age of 50, 60, or 70 and beyond.

For most of modern history, this trend has influenced the workplace, as well. It’s been the norm for workers to retire sometime in their 60s, making room for the advancement of younger generations, who often swell ranks further down the seniority chain and skew the average age of the workforce downward relative to the average age of the overall population.

Living Longer …

For a variety of reasons, this dynamic has changed dramatically in recent years. It’s far less common for children to die before reaching adulthood than it was even 100 years ago. Parents today have fewer children than in years past. The shift from physically demanding labor to a more knowledge-based economy also means that workers have the physical ability to remain in the workforce longer.

… Means Working Longer

AARP’s Kenneth Terrell points to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and projects that by 2024, 13 million people aged 65 and older will still be working. Despite the attention that the Millennial demographic often receives, this older generation will represent the fastest-growing segment of the workforce from 2014–2024.

Terrell says, “While the total number of workers is expected to increase by 5 percent over those 10 years, the number of workers ages 65 to 74 will swell by 55 percent. For people 75 and older, the total will grow a whopping 86 percent, according to BLS projections.”

Increased numbers and proportional representation of older workers in the workforce potentially mean major changes in workplace culture, norms, and intergenerational dynamics.

Impact of an Older Workforce on HR

So, what does this mean for the future American workplace? Here are a few areas of impact for companies and their HR departments to keep in mind.

Recruitment and retention. When the useful working life of employees extends into their 70s and beyond, companies will need to consider new strategies—including opportunities and threats—when making recruitment decisions and focusing on retention strategies.

This is particularly true given the tight labor market and the fact that American companies have roughly a 15% turnover rate, meaning each year, approximately 15% of employees will leave their jobs. In other words, just because a 30-year-old applicant has decades of working potential remaining doesn’t mean he or she will live them out at your company.

Company culture. “OK Boomer” has become something of a rallying cry for disenchanted younger generations frustrated by their perceptions that the Baby Boomer generation is woefully out of touch and just doesn’t get it. It’s a sentiment that has adorned countless memes, T-shirts, and coffee mugs.

But, when this sentiment makes its way into the workplace, it can signal big problems. It’s a sentiment that reflects potential growing tension between older and younger generations that can be particularly toxic when there is such a wide range of ages working together.

Leveraging experience. Consider the level of experience a 75-year-old employee has relative to a 35-year-old employee. That’s potentially 4 decades of additional perspective, institutional memory, and learning and development.

While some of that experience may be rendered obsolete by changing economies and technology, so much of it is still relevant that it makes sense to leverage that experience however possible. This could include mentorship programs, internal consulting, etc., to capitalize on the wisdom and experience of older employees to help mentor their younger colleagues.

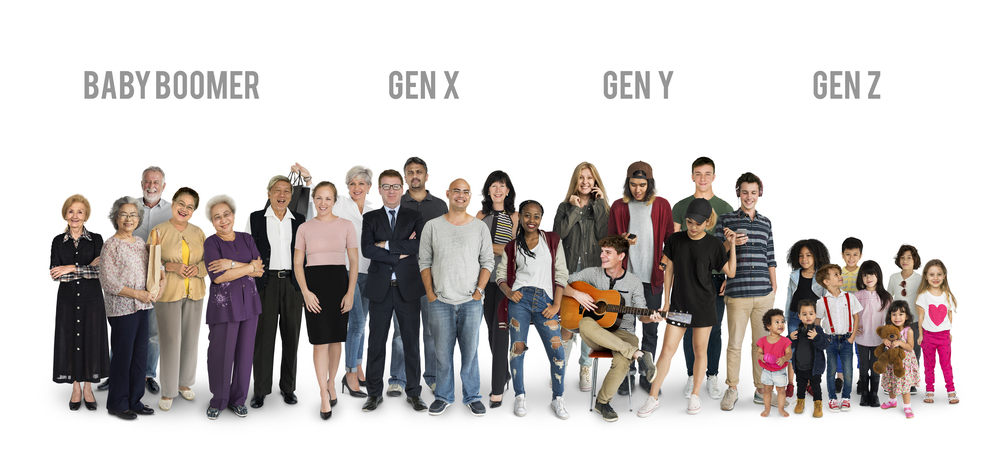

Workforce commentators talk a lot about the impacts of younger workers on the workplace. Millennials and now Generation Z are making up a larger and larger portion of the workforce. But at the same time, at the opposite end of the age spectrum, older workers are choosing to remain in the workforce longer.

All of this means companies need to reconsider the way they think about age in the workplace, from recruitment and retention to workplace culture. Those that don’t could be underutilizing a valuable human capital cohort.